Paediatric ophthalmology is a speciality in ophthalmology concerned with eye diseases, visual development and vision care in children. Various eye diseases affect children in a way that is quite distinct from adult eye diseases, and fortunately most are treatable if detected early.

It is a fact that more than 80% of information a child receives, is obtained visually. Hence, early detection and treatment are both of utmost importance in promoting normal visual development and in preventing significant visual loss.

I will address a few common eye conditions encountered throughout my many years of clinical practice that I would like to share and highlight.

‘Lazy eye’ or amblyopia is reduced vision in an eye that has not received adequate use or visual stimulation during early childhood. Commonly, it results from either a ‘squint’ or a difference in image quality between two eyes due to refractive error as mentioned before. In both cases, one eye becomes dominant, suppressing the image of the other eye. If this condition persists, the weaker eye may eventually become impractical.

Before treating amblyopia, we have to treat the underlying cause first. Spectacles are frequently prescribed to improve focusing of the eyes, and eye muscle surgery is performed to straighten the eyes. Subsequently, amblyopia treatment is carried out by patching or occluding one eye for a period ranging from weeks to years. The idea is to force the ‘lazy eye’ to work, thereby strengthening its vision. Alternatively, topical eye drops may be used to blur the vision of the fellow ‘good eye’ and eminently force the ‘lazy’ one to work, but this is a less successful approach. An amblyopic eye may never develop good vision and may even become functionally blind if not treated early.

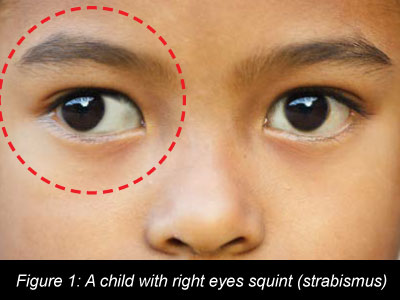

Another common condition encountered is misalignment of the eyes or better known as ‘squint’ (strabismus, Figure 1), whereby, the eye appears crossed, or drifts in respect to the other eye. The crossing may be occasional or constant. Signals from the crossed eye are “turned off” by the brain to avoid double vision and will, later on, lead to ‘lazy eye’ (amblyopia) and or loss of three-dimensional or stereo vision. The treatment depends on the severity and type of squint and encompasses glasses, patching of the eye and even corrective eye/strabismus surgery. It is a misnomer to think that a child can grow out of strabismus on its own and early treatment is imperative.

Abnormal refractive states of the eye such as myopia – short-sightedness, and hyperopia – longsightedness, poses a common problem of late and can occur in children from a very young age. Refractive errors cause incorrect focusing of light onto the retina, leading to blurry images. As a result, the child may complain of frequent headaches, eye strain and difficulty with near or distant vision. Late detection and correction of refractive errors can ultimately lead to lazy eye. Altogether this can be avoided simply by prescribing corrective spectacles.

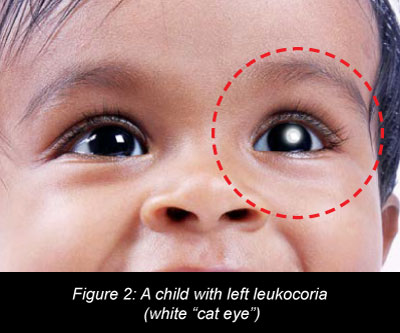

The child may have a white “cat eye” (leukocoria) which is more noticeable in photographs (Figure 2). Amongst the commonest cause of this in children is cataract. A cataract is an opacity of the lens in the eye. It can develop during pregnancy or in early childhood, and it can affect one or both eyes. Other signs to look for in a child with cataracts include abnormal rapid eye movements, eye misalignment, or merely a child who is unable to see, particularly if both eyes are affected. The key difference in managing a child with cataract in comparison to adults is that it is crucial that the child is referred early so that surgical treatment can be carried out without delay to avoid permanent visual loss due to ‘lazy eye’. It is evidenced that the earlier the surgery is performed, the better the visual outcome.

Leukocoria is also an ominous sign of another more serious ocular pathology which is a retinoblastoma. It is imperative to examine all children with leukocoria because of the potential life-threatening nature of retinoblastoma which is the most common eye cancer in children.

Most of the time, vision problems in children are not evident, and the best way to detect them early is to schedule routine comprehensive vision screenings with an ophthalmologist. Nevertheless, parents, as well as teachers, should be aware of signs that a child’s vision is affected such as sitting too close to the television, squinting of the eye or tilting of the head, frequent eye rubbing, excessive tearing or glaring and receiving lower grades than usual. It is advisable that all children should have their eyes screened at six months of age, followed by a second eye exam at age three and once more before starting school. On the contrary, children with risk factors such as the history of premature birth or low birth weight should have their eyes examined earlier than six months of age followed by more frequent eye exams throughout childhood.

Lastly, I would like to emphasise and reassure that most of the eye diseases in children can be preventable or treatable if detected early.

Comments